Are social media bad for mental health? It's the wrong question.

What the historical eras of epidemiology can teach us about tackling a modern problem.

If your social media feeds look anything like mine, they are probably buzzing with alarming reports on the harmful mental health effects of social media themselves. Several thought leaders are driving this conversation. NYU social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has written convincingly on Substack and in The Atlantic about how the teenage mental health crisis coincides with the rise of social media (you can follow along with his literature review here). Clinicians like Oxford’s Lucy Foulkes suggest that an overawareness of mental health problems—both in classrooms and on social media—may cause hypervigilance and safetyism, thereby worsening adolescent’s mental health outcomes.

At the same time, though, rigorous reviews and mega-analyses have actually failed to show strong effects of social media use on mental health. The empirical evidence that Haidt includes in his writings has been argued to be questionable at best. And when my former colleagues from the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health interviewed teenagers about their mental health in a study for UNICEF, the participants overwhelmingly talked about social media as a positive influence in their life. Here’s from the report’s English summary:

One notable finding from the study is that young people experience relatively little stress from social media. This is particularly striking because social media are often identified as being sources of pressure and stress. Young people see this differently; for them, social media offer a lot of benefits as well. Social media constitute a form of social support for young people, which is in fact a key protective factor for mental well-being.

How can we reconcile this apparently contradictory evidence? We’d better reach some conclusions soon, because if social media are indeed bad for us, much hurt could be avoided if we figure out its impact sooner rather than later. Compare this to the health effects of smoking: the Surgeon General already published a report in 1964 stating that smoking was probably bad for your health, but it took several more decades for governments to take real action and stop the spread of lung cancer.

I think we can elucidate what’s going on by recognizing that you can look at public health problems in several quite different ways. Let’s first outline these paradigms briefly, and then see how they are (mis)used to understand social media’s impact on mental health.

1. The four eras of epidemiology

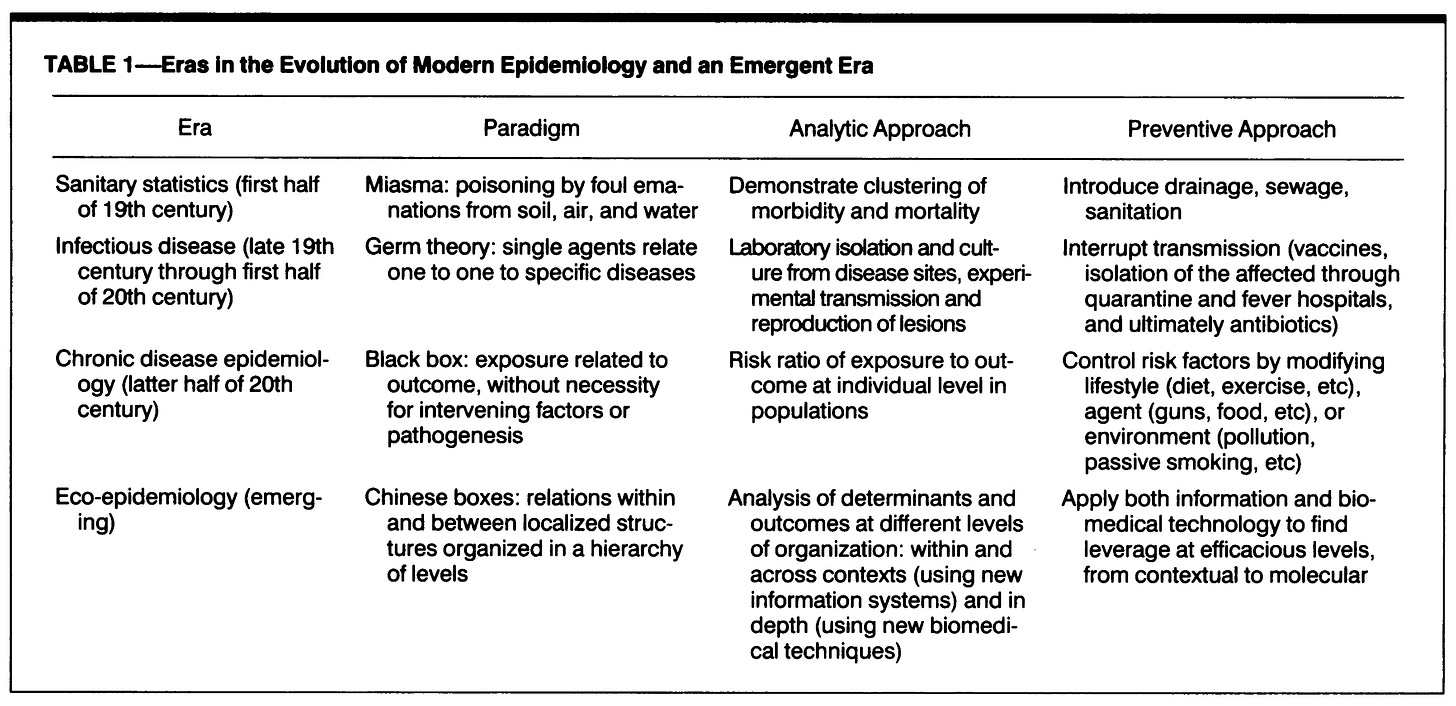

Looking back in time, researchers have identified several different models of thought in epidemiology, the science of population health. Father and son researchers Mervyn and Ezra Susser proposed four eras of this evolution in a 1996 paper entitled Choosing a Future for Epidemiology: II. From Black Box to Chinese Boxes.

The Sussers’ historical progression starts with the era of sanitary statistics, in which we realized that some sickness can come from pollution or poisoning of air, water, and soil. This way of thinking had notable success and, though incomplete and false in some key respects, gave epidemiologists concrete ways to reduce the spread of illness. The classic example is that of London doctor John Snow (not the one from Game of Thrones) who discovered that a cholera outbreak in 1854 was clustered around a contaminated well. Since that time, we know that separating sewage from drinking water is key for public health, and this remains a central goal for human development as evidenced by its place among the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Another noteworthy case is that of Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweiss, who realized that washing your hands before helping deliver a baby was a good idea. The maternal mortality rate in his ward dropped from a staggering 18% to just 2% after his staff started disinfecting their hands with a chlorine solution before deliveries. It’s hard to believe today but this was truly revolutionary stuff, for which Semmelweiss was actually ridiculed by his brethren physicians. The history of public health is a stunning account of how science clashes with culture and how things we now take for granted were vehemently resisted not long ago.

Interestingly, although some doctors in the mid-1800s realized hygiene was important, nobody knew precisely what was unsanitary about dirty hands. This insight only arose during the second era of epidemiology, that of infectious disease. Scientists like Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) started identifying pathogens under the microscope: bacteria and viruses that can cause disease, can multiply, and can be transferred from host to host. This ushered in new methods for diagnosing disease, a revolutionary understanding of how disease spreads, and much better ways of attacking the root causes of health issues. Tried-and-true infection control measures such as social distancing, quarantine, and vaccination have saved millions of lives since the days of Pasteur. We all recently got a taste of this during the COVID-19 pandemic—and again, we also got front-row tickets to the enthusiastic vilification of evidence-based epidemiology.

The third era is that of chronic disease. Chronic diseases are chronic in that they stay with you for a long time, often until you die (sometimes, but not always, from the disease itself). Contrary to the ‘acute’ diseases triggered by infection with a pathogen, most chronic illnesses are non-communicable. They tend to be rooted in a disfunction of a system in your body. In diabetes, for instance, a particular type of cell in the pancreas fails to produce insulin, which severely impairs your ability to control your blood sugar levels. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), blockages in your airways severely reduce your ability to breathe and cause painful coughing fits.

Both diabetes and COPD can be prevented and combatted by modulating your behaviors and exposures such as exercise, diet, and second-hand smoking. This illustrates how the chronic disease paradigm shifted the focus from sanitation and pathogens to personal and environmental ‘risk factors’ that lower or raise the odds of illness. Analyzing these risk factors has helped halt the rise of lung cancer (avoid smoking!), cardiovascular disease (avoid red meat!) and other probabilistically preventable health problems. But this also curiously facilitated a ‘black box’ thinking style in which mapping out the risk factors becomes more important than understanding the mechanism through which illness comes about. As we will see later, this black box thinking impairs our ability to understand—and effectively tackle—the mental health effects of social media.

The fourth era identified by Susser & Susser is something they term eco-epidemiology. This era is perhaps best summarized by stating that multiple causes (or risk factors) of disease interact with each other, and that their relative influence depends on the multiple layers of overarching ‘systems’ or ‘structures’ in which a person is embedded. As field great Nancy Krieger pointed out in a pivotal 1994 paper:

“It is more than a misnomer, for example, to imply that it is simply a persons’s freely-chosen ‘lifestyle’ to eat poorly when supermarkets have fled the neighborhood, or to have a child early or late in life or not at all, without considering economic circumstances and job demands.”

The fact that health outcomes remain vastly different between advantaged (e.g. rich) and disadvantaged (e.g. racially marginalized) groups in the population, despite our best public health efforts, also reminds us that there is more to health than just eliminating singular risk factors like diet or exercise. The ongoing U.S. opioid epidemic makes it abundantly clear that population health depends not just on individual behaviors or traits but on such diverse macro-level factors as the local job market, housing, the availability and affordability of health care, crime, and the power of pharmaceutical companies. All these factors are, sadly, beyond the sphere of influence of any individual.

2. The dominance of chronic disease thinking

Although each era outlined above came with its own epidemiological paradigm, it’s not the case that each era replaced the previous one. Instead, each paradigm remains valuable in its own right even in today’s epidemiology. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, it was clear that the paradigms of sanitation (hand washing), infection (social distancing), risk factors (obesity), and eco-epidemiology (social class) all played important roles in our understanding and control of the disease.

Nevertheless, the different paradigms do compete for our attention. The chronic disease model in particular has been very popular for a while now, and for good reason. Once we figured out how to prevent getting sick from poor sanitation or infections, non-communicable illness such as diabetes and cancer started to take up a larger share of the total disease burden. This led the U.S. Surgeon General in 1967 to declare: ‘The time has come to close the book on infectious diseases. We have basically wiped out infection in the United States.’ Although this famous statement turned out to be hubristic, non-communicable disease did take much of the limelight in recent decades. According to data from the Global Burden of Disease study, the percentage of all deaths worldwide that resulted from non-communicable disease rose from 57% in 1990 to 74% in 2019, steadily replacing communicable-disease death. (The death toll of injuries, meanwhile, stayed pretty much the same at around 8-9% of all deaths—we humans just won’t learn, will we?)

3. Toward a better epidemiology for the online mind

Perhaps because of the dominance of the chronic disease paradigm in the past few decades, researchers like Haidt appear to view social media through this lens. For them, social media use is a risk factor, an exposure, akin to a toxin in the environment or overeating. Under this model, it would make sense that you look for ‘dose-response relationships’ by which an extra hour of social media use each day should cause a proportionally greater risk of mental health problems, and by which such effects ought to be roughly consistent across people. By this model, social media are like smoking: a lifestyle choice that proportionally erodes your healthy psychological functioning; an independent variable you can flip on or off in your statistical model of mental illness.

But this way of thinking about the problem is fundamentally flawed. Social media aren’t a singular ‘exposure’ akin to smoking or eating fatty foods. Instead, they form a highly complex context that facilitates and shapes a host of other exposures and behaviors. More than a risk factor, social media are an environment—in some ways, even a more important one than the town or city in which we live. This is particularly true for young people. They use social media to connect with friends and classmates, to discover their talents, to find work and to sell their work, to educate themselves, to find love, even to organize and resist tyranny. Social standing on social media also translates into critical benefits for everyday life: status, income, connections. Social media aren’t a pastime; they’re a place. In the language of evolutionary biology, social media are the ‘niche’ of the modern human being.

The relationship between social media and mental health, therefore, is much more complex than simple dose-response. And this insight can explain the mixed findings in the literature. One study from the University of Amsterdam tracked social media use (SMU) and self-esteem over three weeks in nearly 400 teenagers, and found that “the majority of adolescents (88%) experienced no or very small effects of SMU on self-esteem (−.10 < β < .10), whereas 4% experienced positive (.10 ≤ β ≤ .17) and 8% negative effects (−.21 ≤ β ≤ −.10)”. A follow-up analysis suggested that momentary feelings like envy and inspiration were pivotal in determining whether teens felt better or worse after browsing Instagram and Snapchat. Other work has reported that teens who use social media “problematically”—meaning for instance that positive and negative social media experiences swayed their mood a lot more than in other kids—were more likely to have lower self-esteem and feel depressed. In the same study, 78% of social media-using adolescents were classified as “no-risk”, meaning they were not affected much by social media use at all.

So let’s forget the dose-response relationship. Saying social media is bad for mental health is like saying living in a city or going to college is bad for mental health. It might be true at the coarsest statistical level—for example, it is well known that schizophrenia is more prevalent in urban populations—but it’s true in an uninteresting way, as it neither teaches us about how mental illness comes about nor gives us realistic handles on the problem. Saying social media is bad for mental health is shirking the responsibility to understand what’s really happening in teenagers’ lives.

What we need, instead, is a social media epidemiology that does justice to the scale and complexities of online life. I don’t know precisely what this should look like, and there’s no space here today to expand on it all that much. But a successful approach should probably try to capitalize on all four paradigms of epidemiology. For instance:

The sanitation paradigm can measure and mitigate exposure to harmful online content;

The infection paradigm can illuminate how mental health issues such as suicidal ideation, eating disorders, and substance use can be transmitted or mitigated via social networks;

The chronic disease paradigm can show us what a healthy online ‘diet’ might look like;

And the eco-epidemiological paradigm can put these risk factors in context and be inquisitive about what it means to be online, rather than just saying we need more or less of it.

With all this I’m not trying to say that social media are harmless—some aspects of online life probably present serious threats to mental wellbeing. Perhaps the nascent “epidemiology for online life” I’m proposing will come up with strict guidelines for limiting social media use in teenagers. But these guidelines will only be effective if we first understand what social media mean for young people. And that is a question worthy of serious and balanced scientific inquiry.

How do you think we can better understand the mental health effects of social media? Share your ideas in the comments or shoot me a message! And if reading this post was worth your time, please give it a like below: it helps others find my work. Thanks!