Data dispatch #5: does money make you happy?

An "adversarial collaboration" between famous scientists sheds new light on an age-old question.

Dear Educated Guessers, for this post I revisited an age-old question: does money make you happy? I’ve always heard the folk wisdom that it doesn’t, but I’d never taken a close look at what the science says. So for today’s post I reviewed three high-profile papers from the field of behavioral economics. Disclaimer: this is NOT the entire academic literature on this issue. But it does give new insights and a lot of food for thought. Hope you enjoy it.

Does money make you happy? How we answer this question might inform all kinds of decisions in our life, from choosing what career to pursue to supporting redistributive tax policies. In a rare solo recording from 1984, Queen frontman Freddy Mercury put in his two cents: Money can’t buy happiness. Was Freddy right?

Operationalizing happiness

To get an answer, we first have to define what we mean by happiness and how we can measure it. In keeping with Ancient Greek notions of hedonia and eudaimonia, researchers often distinguish between two types of happiness: a day-to-day sense of “feeling good” (hedonic happiness or emotional well-being) and a longer-term sense of “life satisfaction” (eudaimonic happiness or life evaluation). For instance, going out to eat sushi with some friends might give you hedonic happiness in that moment, while building a habit of spending time with friends and family regularly and contributing to one another’s lives over the course of decades might give you eudaimonic happiness. To attain eudaimonic happiness we sometimes forgo hedonic happiness, such as when we spend a Saturday studying at the library while your friends are out eating sushi. Conversely, we might sacrifice eudaimonic happiness for hedonic happiness, such as when we give up a meaningful job for a high-paying “bullshit job” that gives us the cash to eat sushi every day yet leaves us questioning the meaning of life at age 45. You get the point.

The hedonic happiness plateau

The next step is to put our question to the test: does giving people money make them happier? Unfortunately, running such an experiment would be very expensive, which is why most research thus far has been cross-sectional. This means that scientists simply try to measure whether richer people tend to be happier (hedonic or eudaimonic) or not.

This is what the legendary behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman (of Thinking, Fast and Slow fame) did with his Princeton colleague Angus Deaton. They published a study in the journal PNAS in 2010 in which they analyzed daily response data collected from 1000 Americans participating in the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index. The participants answered questions about how they had felt the day before (in terms of positive feelings, feeling not-blue, and being stress-free), which represents hedonic happiness; and how satisfied they were with their life on a scale from 0 to 10 (the “Cantril ladder”), which represents eudaimonic happiness. Crunching the numbers, Kahneman & Denton found that higher income was associated with greater eudaimonic happiness: The wealthier participants reported greater satisfaction with their life. Higher income was also associated with greater day-to-day hedonic happiness, but—and this is the key point—only for participants up to the income bracket from $60,000 to $90,000. Above that bracket, participants with higher income reported the same amount of positive feelings, absence of sadness, or absence of stress, as you can see in the three plateauing lines in the graph below:

This “plateau effect” became a mainstay in pop psychology, in part because it fits with two existing theories about emotional wellbeing. The first is the notion that while money doesn’t make you happy by itself, the lack of money can make you unhappy. This isn’t rocket science. If you don’t have enough money to pay your rent or buy healthy food for your kids—as is plausible for the people in the lower pay brackets of the Kahneman study—you’re going to feel bad in your day-to-day life. Indeed, an overwhelming body of research looking at this question from a mental health perspective shows that poverty is a significant cause of depression and anxiety disorders. And while it is possible to have a psychiatric disorder and be happy (psychiatric disorders and mental wellbeing are thought by some to vary on two independent continua), on average struggling with mental illness makes it less likely that you will enjoy good mental wellbeing and hedonic happiness. For more on this, see my earlier post on the “social determinants of mental health”:

The second theory has to do with motivation. I think there is a strong link between intrinsic motivation and happiness, because working on something we care about makes us feel joy throughout our working week. And as a wealth of behavioral research demonstrates, adding money as a reward can actually harm intrinsic motivation in our work. Again, earning too little is demotivating as it distracts us from what we’d like to work on; but a focus on bonuses and extra pay will ironically have the same distracting effect. As Daniel Pink, author of the book Drive: The surprising science of what motivates us puts it in his excellent TED talk: “The best use of money as a motivator is to pay people enough to take the issue of money off the table.” Click here for a nice animated version of that talk.

Breaking through the hedonic ceiling?

So Kahneman’s “plateau” theory fits with some key ideas from social psychology. You’ll understand my surprise, then, when I found a 2021 PNAS paper that falsified the plateau finding!

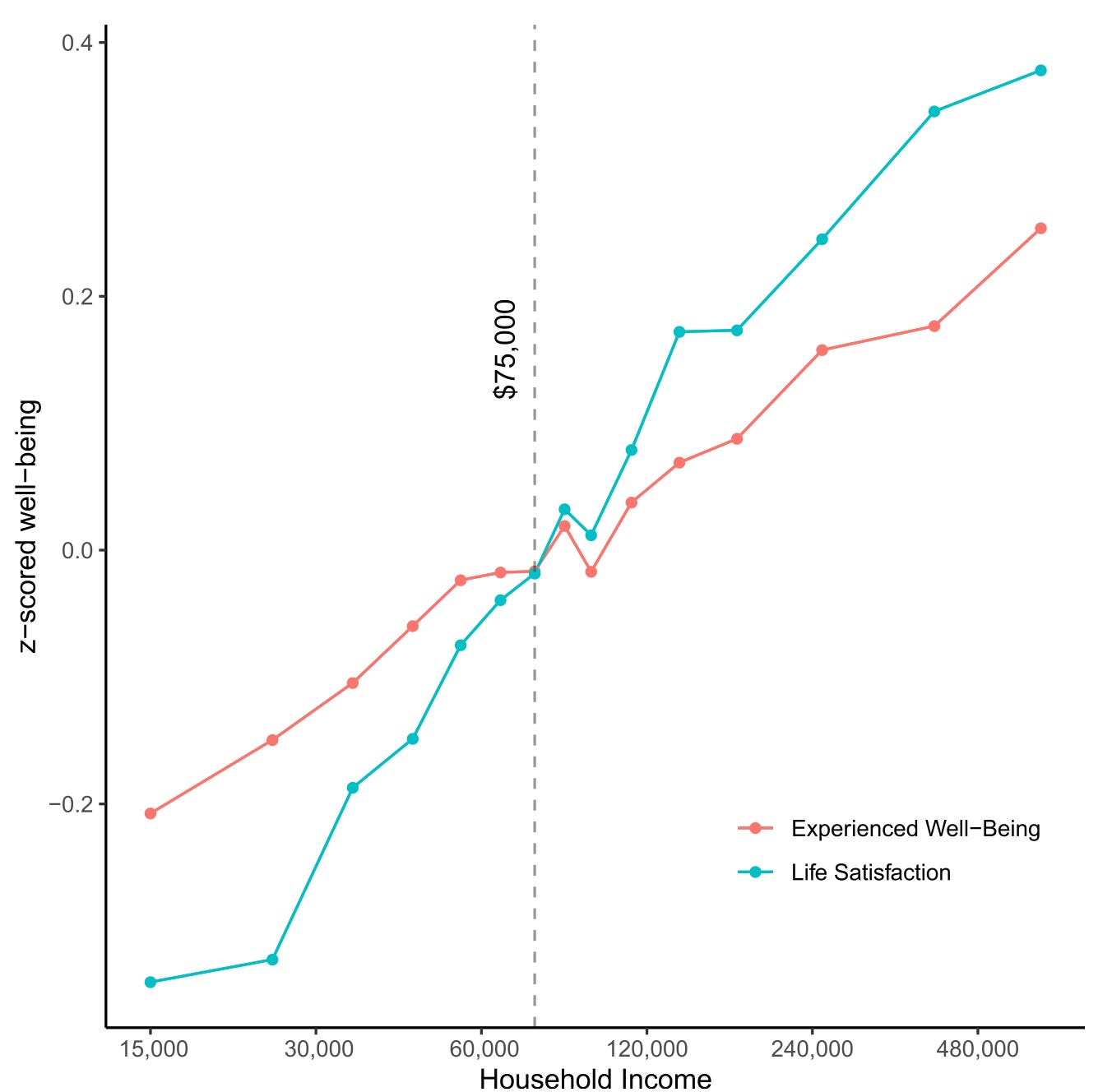

I’m talking about this work by Matthew Killingsworth from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Killingsworth collected “experience sampling” data from about 33,000 U.S. adults. The participants received a notification on their smartphones about three times a day for several weeks, asking them two questions: “How do you feel right now?” on a scale from “Very bad” to “Very good” (hedonic happiness), and “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life?” on a scale from “Not at all” to “Extremely” (eudaimonic happiness). Analyzing 1.7 million data points, Killingsworth reported a consistent log-linear relationship between household income and both kinds of happiness, with no plateau in sight:

Collaborating for truth

Killingsworth’s paper made splash because it went against the widely accepted plateau principle of hedonic happiness. (On the eudaimonic side of the equation, both papers reported the same finding.) Who should we believe, Kahneman or Killingsworth? Luckily for us, Kahneman and Killingsworth were brave enough to embark on what scientists call an “adversarial collaboration” to find out. They published their results in March 2023, again in PNAS, collaborating on this with fellow Penn researcher Barbara Mellers.

The researchers first agreed that they would reanalyze Killingsworth’s data, because asking people about their feelings RIGHT NOW was seen as the most reliable approach, and Killingsworth simply had much more data to explore. They then developed a hypothesis that could explain both papers’ findings: Kahneman’s plateau principle might only hold for the least happy people. Inspiration for this hypothesis was an error in Kahneman’s original measure of day-to-day emotional well-being. The issue was what researchers call a “ceiling effect”. Even with a level of daily wellbeing that was not the highest possible level, Kahneman’s participants already reached the maximum score on his measure (3 out of 3). Think of this as giving an elementary school math test to a high school class: since most of the students would score a 100% on this super-easy test, you can’t tell the average performers from the true math brainiacs. Because of this ceiling effect, variation in hedonic happiness at the top of the income distribution may have remained hidden behind a plateau, with a run-up shaped only by the least happy individuals.

If the new hypothesis were true, the researchers predicted that the least happy participants—the bottom 15% of the 33,000 people in the dataset—should not get any happier above $100,000 (Kahneman’s $90K adjusted for inflation), while there should be a positive relationship between income and hedonic happiness for people with a higher happiness level. The researchers split Killingsworth’s data by happiness subgroup, and voila: While hedonic happiness went up with income for most happiness groups, there was a clear plateau above $100,000 annual income for the least happy 15% of the population. These results suggest that for people who are unhappy, earning more than about $100,000 is not associated with increased day-to-day emotional well-being. However, for people that are in the 30th percentile of the happiness distribution or higher, higher income does correlate with greater hedonic happiness.

Conclusions

Where does this leave us for our original question—does money make you happy? Here are my takeaways.

All the above evidence is only correlational, not causal: it might be that more money makes you more hedonically happy, or that happiness allows you to make more money, or that there is a third mechanism facilitates both happiness and money-making potential (e.g. a privileged upbringing). So we can’t say that “money makes you happy”, only that “people who make more money tend to have greater day-to-day emotional well-being”. That doesn’t sound as good, but it’s more true. Perhaps it’s enough to make you want to boost your annual income.

Importantly, though, money is not the ONLY thing that correlates with happiness. Indeed, the relationship between income and happiness found by Kahneman and Killingsworth is relatively small. The authors themselves write: “The correlation between average happiness and log(income) is 0.09 in the experience sampling data, for example, and the difference between the medians of happiness at household incomes of $15,000 and $250,000 is about five points on a 100-point scale.” In a practical sense, we should ask ourselves: is a 5-point increase on a 100-point scale worth the sacrifice of obtaining a high-paying job? Or are there other, more effective (and achievable) ways to boost your happiness in life?

Building on this—I have the intuition (but correct me if I’m wrong) that the least happy people might be the most motivated to try to boost their daily happiness by earning more money. Since the 2023 study shows that the most unhappy people don’t benefit above $100,000, we might suggestively conclude that high-paying jobs are wasted on the unhappy. Ironically, the happiest people (who might not be quite as concerned with earning a lot of money) might be best served by earning a bit more cash.

To me, the most surprising finding throughout these papers is the consistent positive relationship between income and eudaimonic happiness. This is paradoxical to social psychologists, because they know that high wages can harm intrinsic motivation for work and thereby impede fulfillment in life. One explanation could be that we tend to evaluate our own lives through the eyes of others: if you achieve high social status through your earnings, you might use this social evaluation to anchor your own satisfaction with your life. Another possibility is that this is a typically American phenomenon, in which case eudaimonic happiness in a less capitalist society like France might be derived from other sources than money or work-related achievement. Worldwide data would be helpful to tease these explanations apart.

Finally, I think the 2023 paper is a really cool example of academic self-correction. It shows that even a Nobel Prize-winning scientist (Kahneman) can publish a paper in a world-class journal (PNAS), get cited 4000 times, and admit 13 years later that he made a fundamental mistake in his measurements.

What do you think, does money make you happy? Let me know in a comment in the Substack app or website! And if you liked this post, give it a like and consider sharing it with a friend.

Over the next couple of weeks I’m trying out a biweekly publishing schedule to make more space for my book project on uncertainty. So there will be more Educated Guesses, but at a slightly longer interval than you’re used to. Thanks for reading!

~ Jeroen

This is fascinating, thank you. I think you're insufficiently sceptical about the research, though. It's not just that it doesn't establish a casual relationship, it's that the questions asked are unlikely to yield any useful information.

Is someone rich supposed to be happy, do you think, or do you think other people are likely to think? If you're asked if you're happy by a stranger, what answer would you feel is most appropriate for someone in your position in life? If asked by a variety of different types of stranger, of varying levels of status and connection to yourself, how would your answer alter? What role do guilt, entitlement and shame have in your answer?

This research is like trying to work out whether an animal is currently on fire by asking people what they think others might say about how red the animal looks as compared to any other animals they can think of. It's stupid on so many levels that any results you get will be self-evidently worthless.