Dear Educated Guessers, some exciting news: on May 6-8 I will be giving a talk and a workshop at the 8th Annual One Mind at Work Global Forum in Napa, California. The event brings together mental health leaders from a number of large companies as well as independent experts to exchange insights on fostering workplace wellbeing. The theme of the meeting is “Doubling down on mental health and wellbeing in times of uncertainty”, which dovetails with the research I’m doing for my forthcoming book on the uncertainty epidemic. So I was asked to speak on what I see as an uncertainty paradox: can we fulfill a growing need for predictability and control in an increasingly uncertain world?

To get warmed up for this theme, I wanted to share with you some key insights from the extensive scientific literature on workplace mental health. In a short series of posts, we will zoom in on the impact of uncertainty and control on work stress.

Today’s pair of studies were performed decades apart, but yield a clear common insight: it is not just workload, but also lack of job control that gives rise to stress and burnout.

Job control in 1970s Sweden

The first study was published in 1981 by Columbia University’s Robert Karasek and a group of colleagues from the US and Sweden. The researchers were interested in symptoms of coronary heart disease (CHD) among working people. CHD was (and is) a very common health issue and was at the time increasingly being linked to psychosocial causes, such as stress at work.

Luckily, a big representative study of the health of the Swedish population was conducted in 1968 with a follow-up in 1974, and from this data set the authors could extract a sizable subgroup of 1461 male workers (back then men made up 83% of the Swedish workforce).

These participants answered questions about characteristics of their jobs, with a specific focus on two aspects:

Job demands, measured by items like “Is your job hectic?”

Job decision latitude, which was meant to reflect the individual’s control over job-related decisions. This included, for instance, the items “Is your job repetitive/monotonous?” (less latitude) and “Can you leave your job for half-an-hour for private errands during working hours without telling your supervisor?” (more latitude)

The researchers found that symptoms of coronary heart disease were most prevalent in workers who had a demanding job and experienced low decision latitude in their work. These results were obtained even when statistically controlling for known causes of cardiovascular illness, such as smoking and obesity.

Put differently, the harmful health effects of a demanding job can be offset by control over the way you organize and carry out that work.

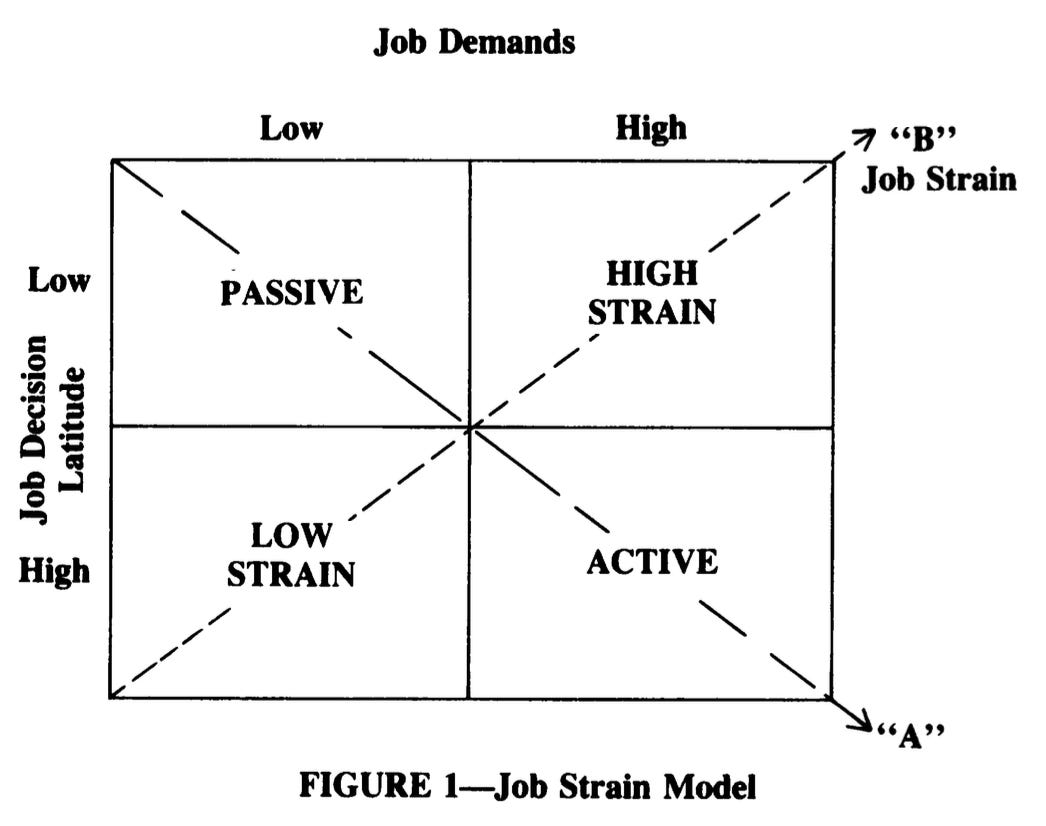

These results led Karasek and colleagues to develop the job strain model. High demands and low decision latitude were thought to create high strain, resulting in cardiovascular and mental health issues. This model is the claim to fame for Karasek, who is now an emeritus professor at the University of Copenhagen.

Although it established Karasek’s model well, the Swedish study had some limitations. One obvious issue is that there might be a host of pre-existing differences between workers who end up in high-control jobs and workers who end up in low-control jobs. It is virtually impossible to measure and statistically control for all these differences, so the predictive value of job control for CHD might be confounded by (statistically ‘contaminated with’) other, unseen causes.

This is one of the reasons why the gold standard in epidemiological research is the randomized controlled trial (RCT), in which the variable of interest (in this case job control) is manipulated in a randomly selected subset of participants, whose health outcomes are then tracked over time.

The RCT

Fast forward 35 years, and the RCT is here. It’s 2016, and a team led by University of Minnesota sociologist Phyllis Moen publishes a report that puts Karasek’s prediction to the test in a field experiment.

Moen and colleagues gathered data about 453 workers at a Fortune 500 IT company. A random selection of teams in the organization was assigned to a so-called “STAR” intervention (“Support. Transform. Achieve. Results.”), which was designed to promote control over work time and supervisor support for employees’ personal and family life. Here’s from the paper:

STAR aims to (1) increase employees’ control over their work hours and schedules and (2) increase employee perceptions of supervisor support for employees’ work and family/personal lives. STAR’s third goal, tied to research on the organizational rewards associated with “face time” and long hours, is to reorient the work culture toward results, rather than hours at the workplace (Kossek et al. 2014). […]

STAR facilitates new practices, such as increased options to work at home and flexibility to shift one’s schedule, but also emphasizes that employees have control over when, where, and how they do their work and that managers and co-workers support their efforts to address family and personal responsibilities.

Moen and colleagues randomly assigned work teams to this STAR intervention or usual practice. At the start of the study, these two groups (logically) were no different in terms of mental health or subjective well-being.

But one year into the transformation, employees in the STAR group had significantly lower levels of burnout (p < .001), perceived stress (p < .05), and psychological distress ( p < .05), as well as noticeably higher job satisfaction ( p < .01). The effect sizes were modest, but not negligible: burnout rates in the STAR group were about a third of a standard deviation lower than those in the usual practice group (in technical terms: Cohen’s d = 0.36).

Follow-up analyses suggested that these positive effects were reached by realizing greater employee control over work schedules and fewer conflicts between work and family duties. Karasek’s hypothesis was confirmed.

Implications

There’s a lot more to be said about these studies. One interesting difference is that Karasek measured CHD while Moen measured mental health and wellbeing. In my reading of the literature, there was a ton of interest in cardiovascular disease as a consequence of stress in the 1970s-1980s, while today we tend to speak about stress much more in terms of mental health. Perhaps this has to do with the destigmatization of mental health problems in general.

Second, while Karasek only included males, Moen included both males and females and found much greater beneficial effects of job control in females. This reflects the changed nature of employment in the last four decades, with many more women entering the labor force and caregiving duties being distributed more evenly over the genders. Indeed, recent studies tend to focus specifically on work-family conflict as a result of low scheduling control (when people work), while older work emphasizes the control employees have over how people work.

With these caveats in mind, though, the papers trace a common thread through the workplace mental health literature. Job strain is determined not just by how much you work, but also by how you work, and specifically by how much you’re allowed to choose how you work. If you’re in charge, it’s much easier to handle stressors than if you’re just trying to survive at the whim of your superiors.

It’s interesting to reflect on these findings in light of the work-from-home revolution that was sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, work from home has given workers much more freedom in balancing work and family duties, which has already led to positive effects for workers who have families. For employees who aren’t parents, though—and in particular for those early in their careers—the effects might be very different.

Furthermore, the internet has ironically also given more opportunities for your boss to control your work, reducing the subjective sense of control. In the past, a micromanaging boss might have looked like Bill Lumbergh from the cult classic Office Space (a must-watch—see video below). Once you’re away from your cubicle, Lumbergh can’t get to you. But today, it is not uncommon to receive emails, Slack messages or even texts to your personal phone after hours or on the weekend, making you feel as if you’re never away from your desk. The effects of this change on mental health are still being chronicled by epidemiologists.

So: what do you think? Is sense of job control as important to mental health and wellbeing today as it was in the 1980s? And do you feel more or less in control when you work from home? Share your insights in the comments below. And if you liked this post, let me know by leaving a like.

Next week we will zoom in on another critical aspect of jobs: the balance between efforts and results. Subscribe now to never miss an update.

A sense of control or ownership is absolutely necessary to enjoy one's job. Even a small thing like being able to listen to music when doing a menial task can have a big impact on work pleasure. Letting employees work from home in my view is essentially the employer letting go of a certain degree of control. There has to be trust that even when not observed, the employee will still do their job. In a sense that is giving an employee more responsibility and control over doing their own work.

Precisely what I needed to read at a complicated junction in my own working life... One fascinating (albeit frequently aggravating) outcome of my COVID-19 pandemic experience is the way post-COVID syndrome (formerly known as "long COVID") and burn-out appear to go hand in hand. My recently building frustrations with my current job's lack of latitude (and, looming over it all, frustrating lack of impact/purpose) have resulted in a relapse of post-COVID syndrome symptoms, and my current sick leave makes me reflect as much on the particulars of my body as on the specifics of the job in question. Having read your analysis, I feel emboldened in the idea that the "how" of a job is just as crucial to your professional (and private) wellbeing as the "what" of it — and, perhaps for future study (conducted among Millennials only?), the "why" of it all...