The world has a bundle on its head

How a sticky self-concept prevents us from leaning into change

Dear readers, thank you for your support for this newsletter so far. It’s been so much fun (and a little scary) to publish each week and in English, and receiving your responses keeps me going. I appreciate every subscribe, e-mail, like, comment, and share.

It particularly meant a lot to me when I had my first paid subscriber this week—thank you! All my content is totally free for now, but with a paid subscription you can help me free up time to write sharper, more thoroughly researched essays.

Before diving into today’s issue, I wanted to share with you that I received some more fantastic news on Tuesday: the Lira Foundation in the Netherlands has decided to fund my new book project. This allows me to commit most of 2024 to researching and writing on a topic that connects much of my previous work in neuroscience and psychology: dealing with uncertainty. Much more on this theme in weeks to come. . .

This is good news for our newsletter too, because I’ll use this platform to log my progress in the form of essays and data dispatches. And most importantly, I want to use An Educated Guess to learn from my readers and stimulate debate. So if you are not yet subscribed, please join to stay in the loop, and please share this newsletter with anyone who might be curious about uncertainty.

And now, back to our regularly scheduled programming.

Act 1. A bundle of advice.

I recently listened to episode 806 of the unbeatable podcast This American Life. The ep is all about “people on the verge of a big change, not wanting to let go.” It struck me that this phrase says more about our world today than we are usually willing to admit.

Sandwiched between two segments on quitting smoking was a piece about quitting a relationship. We hear an audio version of an advice column called Dear Sugar, in which a reader shares her apprehension about leaving her boyfriend of six years.

The advice columnist, Cheryl Strayed, responds by recounting her own experience with her ex-husband. She was living in London with him at the time, doing under-the-table work, and they were barely scraping by. She somehow felt that this situation wasn’t right for her, but was not ready to admit to herself that she needed to get out.

One day, while Cheryl was on her break at work, an old woman came up to her on the street to talk to her. They became friends and this woman kept coming back each day. Cheryl told her then-husband about this woman, but they had never met all three. Until, one day, then-husband and the old woman visited at the same time. They chatted, and after the woman left, then-husband exclaimed: she has a bundle on her head!

And then we laughed and laughed and laughed so hard it might to this day still be the time I laughed the hardest. He was right. He was right! That old woman, all that time, all through the conversations we’d had as I sat on the concrete patch, had had an enormous bundle on her head. She appeared perfectly normal in every way but this one: she wore an impossible three-foot tower of ratty old rags and ripped up blankets and towels on top of her head, held there by a complicated system of ropes tied beneath her chin and fastened to loops on the shoulders of her raincoat. It was a bizarre sight, but in all my conversations with the man I loved about the old woman, I’d never mentioned it.

[…]

I was crying because there was a bundle on the old woman’s head and I hadn’t been able to say that there was and because I knew that that was somehow connected to the fact that I didn’t want to stay with a man I loved anymore but I couldn’t bring myself to acknowledge what was so very obvious and so very true.

Cheryl concludes by writing: “You have a bundle on your head, sweet pea. And though that bundle may be impossible for you to see right now, it’s entirely visible to me.”

Advice columns are a pretty niche (and possibly dying) genre, but this one raises a broadly applicable question. What makes it so hard to acknowledge a bundle on your head?

One answer lies in the notion of self-concept. The sociologist Morris Rosenberg famously defined self-concept as “…the totality of an individual’s thoughts and feelings having reference to himself as an object.” Put simply, our self-concept is the collection of beliefs we have about who we are as a person. If you have a bundle on your head that you’re not acknowledging, there is a true aspect of you that you haven’t incorporated into how you see yourself.

The interesting part is that the self-concept isn’t just a dry set of beliefs; it has huge implications for motivation and well-being. For one, psychologists have proposed that people are deeply attached to their self-concept: we tend to act in accordance with it and try to maintain it in the face of challenging evidence. This is referred to as the “self-consistency motive”, a concept that dates back to Ur-psychologist William James (and has a long history in the self-help world). If the bundle on your head is not part of your self-concept, you’ll act as if it doesn’t exist. And conversely, if you are not acting on an important problem in your life, it might be that you first need to change your self-concept to incorporate the big ol’ bundle on your head.

Forgive me for milking the metaphor, but since I wrote about climate change last week it has occurred to me that the world has a bundle on its head. In the post, I described how even 1.5 degrees of global warming relative to pre-industrial times (which we have almost reached by now) will make home uninhabitable for hundreds of millions of people. And yet, even though most of us have been exposed to years of news about climate change, our image of ourselves as a planet has barely changed. Our collective self-concept is sticky, highly resistant to change.

Let me give you an example.

Act 2. High temperatures in the low countries.

Walking around the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, you are drawn to a muted painting by Hendrick Avercamp named Winter Landscape with Skaters (1608). Little figures stumble around on a frozen Dutch lake, playing hockey and goofing off in 17th-century outfits.

Avercamp specialized in painting snowy scenes like this one and his works have become emblematic for how we see the Netherlands. When asked about typically Dutch customs, for instance, many will mention ice skating. Fittingly, the little country has historically dominated Olympic speed skating, winning 2/3 of all gold medals in Sochi in 2014. And it’s not just the Dutch who believe that ice skating is a key part of their culture; it’s everyone. Here is a picture of a “typically Dutch winter activity” as generated by DALL-E, OpenAI’s program that produces pictures based on a model of all the world’s knowledge:

The Dutch obsession with ice skating is perhaps best illustrated by the ultimate skating competition: the Elfstedentocht (Eleven Cities’ Tour). This one-day, 200-kilometer race passes all eleven historical cities in the northern province of Friesland. When it happens, the whole country comes to a standstill, and the winners are celebrated as heroes.

But here’s the kicker: the Elfstedentocht has not happened in 26 years. It only takes place if the canals connecting the eleven towns freeze over with a thick enough ice sheet (specifically: 15 centimeters or more), which has not happened since 1997. And experts warn that it may never happen again since it’s simply not cold enough.

To illustrate this point, I pulled temperature anomaly records in the town of Winsum, at the geographic center of the Elfstedentocht route, from the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Since most Elfstedentochten took place in February, I focused on this winter month. Temperature anomalies are reported with respect to the 1991-2020 average; cooler years are blue, warmer years are red.

As you can see, the Elfstedentocht has historically only taken place in the coldest years. (An exception is the 1996 Elfstedentocht, which happened in early January and so is not represented well by this graph.) In the new millennium, climate change has all but erased such bitterly cold months. The negative spikes needed to make all of Friesland freeze up have become exceedingly unlikely. As a sad solution to the problem, an alternative Elfstedentocht has been held in the Austrian mountains each year since 1989.

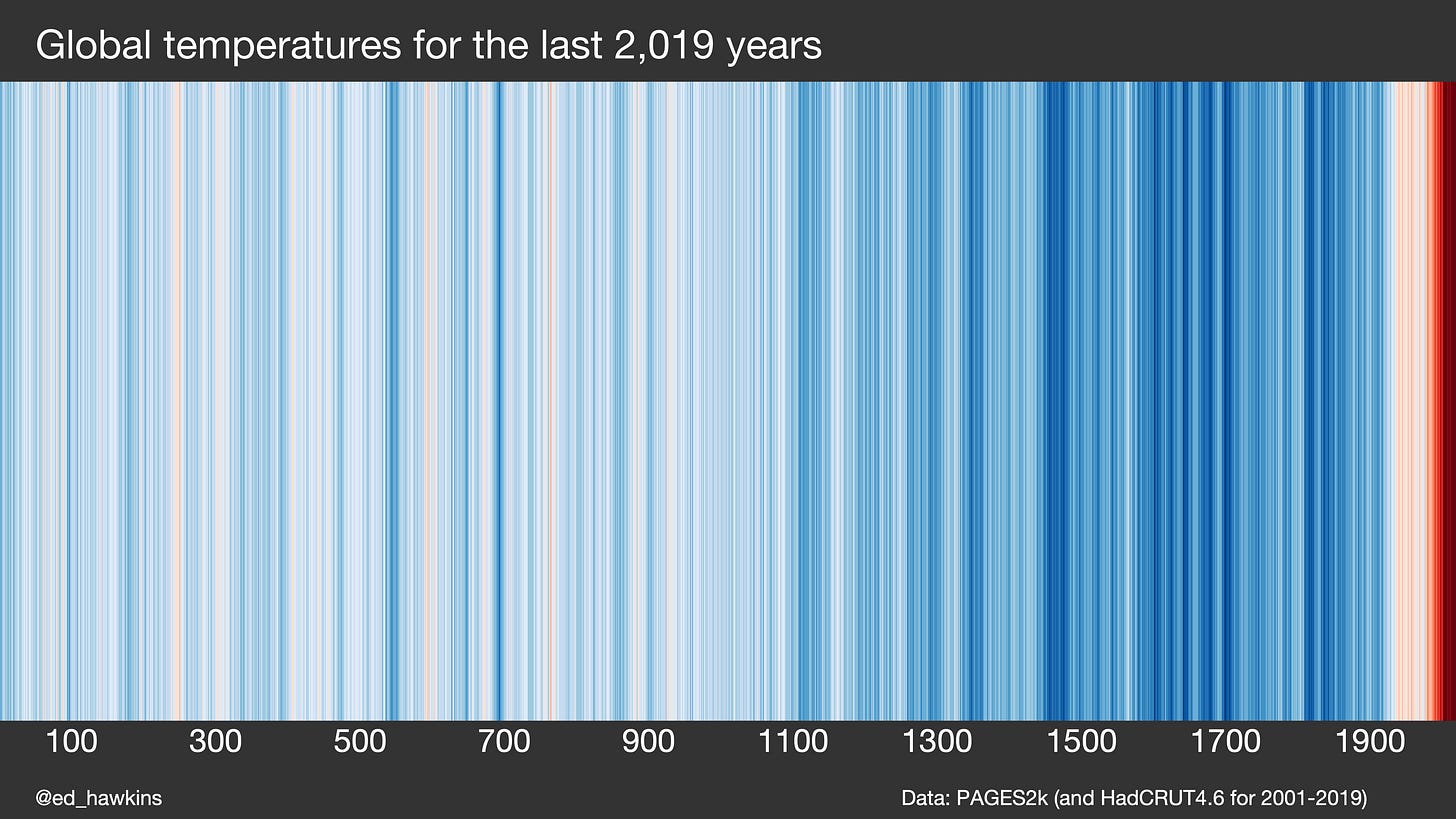

If we zoom out a little more, we see why Hendrick Avercamp’s Holland actually looked nothing like what we have today. The painter lived during one of the coldest periods in Western Europe in recent history. Known as the “little ice age”, this period spanned from roughly 1500 to 1900 CE and saw about 0.2 degrees Celcius global cooling relative to the preceding centuries. You can easily spot this period in the familiar “barcode” image below, created by climate scientist Ed Hawkins. While we currently live in the dangerously red zone to the right of the image, Avercamp spent his life painting Holland during its darkest blues—and this is the period that remains, to this day, iconic for our country.

Act 3. Action needs optimism.

Of course, the Netherlands are not the only country losing a key cultural feature due to climate change. In the French Alps, ski areas are closing for lack of snow. Dry spells in Spain are ruining the traditional olive oil industry. Coastal houses in the United States are washing into the sea. And yet, these countries are failing to reduce their carbon emissions to the levels agreed upon in the Paris Agreement.

I suspect that inaction in the face of these monumental changes results from our sticky self-concept as ice skating, skiing, olive oil-producing, or coastal-living peoples. It’s just like Cheryl’s quagmire in London: if you don’t incorporate your problems into your concept of yourself, you can’t even begin to address them.

Luckily, changing our self-concept doesn’t mean sitting down at a desk and frowning hard to wrap our heads around the dreadful facts of climate change. Self-concepts are better updated using optimism, for optimism soothes the fear that keeps us from seeing the bundle on our head. One initiative that’s already trying is Inner Development Goals, an NGO that attempts to grow the psychological skills we need to “deal with our increasingly complex environment and challenges”. And I’m curious about other ways to embrace climate adaptation with a view to its gains, not its losses.

Let me leave you with Cheryl Strayed, who casts the same message in the sugary style that behooves an advice column:

“You aren’t torn. You’re only just afraid. […] The end of your relationship with him will likely also mark the end of an era of your life. In moving into this next era there are going to be things you lose and things you gain. Trust yourself. It’s Sugar’s golden rule. Trusting yourself means living out what you already know to be true.”

Next week: another data dispatch.