Why I'm moving my research online

Substack allows for an exciting, new, participatory social science--one we desperately need

There’s a new term buzzing around the internet: metacrisis. It implies that underneath the crises of our time—artificial superintelligence, climate change, political polarization, economic instability, you name it—there is a broader issue with the fabric of our society that drives all these problems.

If there really is a metacrisis I don’t know (I’ll make time for it in a future post). What I do know for sure is that we are living in times of unprecedented complexity and change. Just let these disparate data points sink in:

Today, more people than ever live in a country other than the one in which they were born (UN)

The amount of new information created worldwide grows by 20% annually—and each year 98% of it is deleted forever (Statista)

The ancient glaciers in Switzerland have lost 10% of their volume in the last two years; the same degree of loss occurred between 1960 and 1990 (Guardian)

Changes like these will touch all our lives. How should we relate to and deal with them?

This question demands analysis and answers from the social sciences. But in my experience, classical academic research has a limited ability to solve real-world problems. And the analyses you read in the papers are limited to a narrow range of policy options, which are hardly relevant to us as individuals.

This is why I started this newsletter. I want to explore what it looks like to realize a new kind of social science: one that focuses on application in everyday life, embraces complexity, and capitalizes on the curiosity of the community.

I hope you will join me.

In the post below, I will explain my own reasons to engage with this new kind of research and why I think it’s needed. But if you don’t feel like reading a long slab of text, just subscribe now, for free, to receive future posts and join the conversation in the comments.

A little Reformation

I have wanted to be a scientist for as long as I can remember. I have always loved learning, tinkering, and sharing ideas. When I was nine years old, I wrote in a school project that I wanted to be “prof in a lab” when I grew up. And for a while, it looked like I might actually become one. I earned a PhD in a growing field, cognitive neuroscience, and landed a postdoctoral research position at a great university. I had the great pleasure of working with some of the top minds in experimental psychology, some of whom became friends. I published my work in some famous journals and got to see my ideas get cited and used by others to some respectable degree.

But toward the end of this traditional academic trajectory, something felt amiss. Not that it was too much work, too hard, or too boring—I still very much enjoyed the day-to-day rhythm of lab work, data analysis, and teaching. But my excitement about lab experiments had begun to shrink because I had started to question how much useful knowledge we could actually glean from them. Two trends gave rise to this skepticism.

First, as was the case for many other researchers, my unease was fed by the ongoing replication crisis in psychology. This crisis started around the time when I entered graduate school in the early 2010s. Some trace the beginning back to a cheeky article by Cornell professor Daryl Bem, in which he proved that clairvoyance was real. Bem’s study participants were able to intuit with surprising accuracy which set of curtains on a computer screen had an erotic picture behind it, even though the locations of these pictures were drawn randomly. Bem showed, using commonplace experimental methods and statistical tools, that his participants could actually “feel the future”—which made us all really nervous about the reliability of those methods and tools.

Sure enough, a landmark paper soon demonstrated that with routine research methods, researchers were much more likely to draw untrue conclusions than we had thought we were. Suddenly nobody knew which of the many foundational studies in experimental psychology, which were carried out using these methods, reported a factual conclusion or a bogus one. When a huge team of international scientists decided to find out, the sobering result was that about 60% of findings did not hold up when you repeated the study.

For more on how the replication crisis shaped psychology and psychologists, read the wise and funny

over at Experimental History.

My skepticism was further fueled by a startling lack of correspondence between laboratory behavior and real-world outcomes. To me, psychology is valuable to the extent that it can explain and improve the human condition. But laboratory tasks are often so far removed from the real world that they end up saying disappointingly little about how we experience everyday life. This concern has been raised about some really high-profile theories in social psychology, such as implicit bias. It became personally meaningful to me when two economists published a clever study on some of my favorite experiments: economic games.

In economic games like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, we measure how social principles such as selfishness, altruism, and trust determine people’s choices when they play for real money with other participants. Behaviors in these games are thought to reflect stable, enduring moral traits of individuals—but few scientists had bothered to check whether they had any relationship real-world moral fiber. So these two economists followed their participants out into the real world after they had played economic games in the lab at the London School of Economics, secretly exposed them to a real moral choice (e.g. dropping a bunch of pens to see whether they would help pick them up), and noted that whether a participant was kind in the lab was not at all predictive for their prosocial behavior in the real world.

So even if you were able to run a lab experiment that replicates perfectly, it might not say anything about actual human behavior. What’s the point?

These two trends sent me into a crisis of faith. Cynical, I started to see experimental psychology as a self-referential, self-sustaining system that actually made few useful claims about the outcomes I cared about: everyday altruism, cooperation, polarization, mental health, and happiness, to name a few. This system did not excite me anymore.

As you can imagine, I felt a great deal of dissonance between my early-life goal of being a professor and my hunch that the traditional academic path was not for me. But to my surprise, this dissonance did not push me away from research; it only drove me to approach it in a different way. A little Reformation to resolve my crisis of faith, if you will.

Over the past 3 years, I have landed on three pillars that make science worthwhile for me. These pillars motivated me to start this newsletter, and they might convince you to join the conversation.

Pillar 1. Application.

A key outcome of my crisis of faith was to refocus my research on real-world outcomes. Instead of asking how I could produce consistent results in the lab or convince my coworkers that I was very smart, I wanted to ask how I could produce insights that would make a difference to other people.

Many psychologists of course already did this even before the replication crisis, but for me it was an eye-opening experience. I started working as a researcher at the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (the Trimbos Institute). Here, the goal is not to publish as much as possible, but to produce concrete advice that feeds into the health and economic policies that affect all of our lives. This also means embracing a wider variety of research methods, including qualitative approaches, and honing a humility that keeps you from overstating your conclusions.

This is far removed from the way experimental psychologists traditionally try to predict real-world outcomes and inform policy with their work. One example is the article published by a team of high-profile social and behavioral scientists in the early days of the coronavirus (Spring 2020): Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. This highly-cited paper relied on experimental research to suggest, among other things, that governments should address the public in collective terms (‘us’) and communicate via people that are credible to diverse audiences. These wisdoms were derived from laboratory studies evaluating them in highly controlled settings, mixed with a healthy dose of common sense.

Soon after, a comment was published by a more critical team of colleagues: Use caution when applying behavioural science to policy. Using examples from the empirical crises I highlighted above, these behavioral scientists admitted: “the way that social and behavioural science research is often conducted makes it difficult to know whether our efforts will do more good than harm.” This placed a necessary warning label on the earlier article.

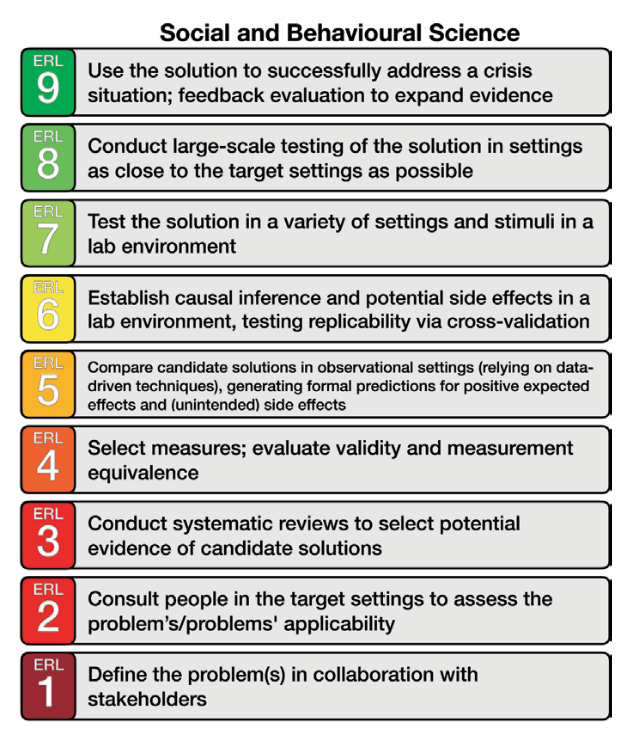

For our purposes, the most interesting part of the critique was a 9-step model for how ready social science evidence is for application. Based on a similar approach for the application of technical research by NASA, this model prescribes that before we can hope to apply a given psychological principle, it needs to be fully understood in its naturalistic context.

What struck me about this picture is that most of experimental psychology seems to live on level 6. It skips over 1 through 5 and rarely reaches 7 or higher. Now, I’m not saying that level 6 is not important—it definitely is. But what good is it if we don’t cover the other bases, too?

It’s time we start taking the other steps of this application model for social science. This means:

Replace reductionism by an effort to map contextual factors that matter for stakeholders of a given phenomenon;

Stop thinking in point predictions on singular variables (e.g. “a stronger social norm = more of the desired behavior”) and start thinking about multidimensional control (e.g. “setting the majority of relevant contextual factors within the right range = higher likelihood of the desired outcome”);

Invite input from all fields of research, not just your own.

Psychology departments and grant agencies don’t like these things: they want clear-cut research that stays in its lane. But by taking our research online, we can climb out of our silos and learn from all domains of human understanding. With newsletters like these, we can broaden our horizon and let complexity back into social science.

Pillar 2. Complexity.

When shifting into applied research, you immediately notice the a trade-off between applicability and precision. Since we’re not in laboratory land anymore, we lack the experimental control needed to isolate individual aspects of human behavior. Instead, we must see human behavior in its messy, multidimensional context.

Consider the economic game example I mentioned before. While we are very good at describing economic game behavior in the lab (for instance with computational models I developed here and here), these descriptions end up unable to describe how people act in the real world. The models lack contextual information, which ruins external validity.

This underscores the importance of parsimony in the sciences. Providing a parsimonious explanation for something means that you describe it with just the right level of complexity. You don’t oversimplify things (because then you’d be wrong more often than needed), but you don’t overcomplicate them either. You avoid using too many elements, words, or components of a model when accounting for a given observation. You might recognize this principle as Occam’s razor.

When you’re in experimental psychology, you have the feeling that you’re hitting the parsimony sweet spot all the time with elegant models of human behavior that outperform previous theories. After all, your (more elegant) explanation accounts for the same (or more) amount of behavior in the lab! But the economic game results show that when putting the same humans in an everyday context, our predictions fall apart. When zooming out and viewing human behavior in context, the parsimony meter of experimental psych turns out to be totally off.

In my view, the best way to recalibrate our parsimony meter is to democratize the process of question-asking. An online forum like this newsletter is an ideal way to collectively form research questions, let them simmer in their natural context, and answer them while keeping reality in mind. By doing so, we can add realism to social science—and gain a tool to tell right from wrong in the process.

Pillar 3. Participation.

Application and complexity both call for a final pillar: participation of stakeholders in research. I began to see the value of this when I was involved in a large consortium project studying the impact of covid-19 on mental health. We had two research questions: 1) How did covid-19 impact the health of vulnerable populations in the city of Utrecht? and 2) What policies or practices could alleviate the adverse effects?

The focus on real-world application forced us to embrace complexity and throw prior lab findings out of the window. When we asked people who struggled with homelessness, debt, or psychiatric illness what their life was like during the pandemic, we heard nothing about the factors commonly linked to population mental health (such as stress or social media addiction). Instead, we learned for instance:

That overly complex public health messages led some parents to overcorrect to the point of washing their children’s school backpacks with disinfectant, which sustained anxiety;

That healthy and resilient 20-somethings suddenly became vulnerable when their transition from college to work life was disrupted, as they were highly dependent on others for structuring their life;

That some people who had long been struggling with loneliness felt more understood now that everyone was stuck at home.

Learning this stuff required including stakeholders in the research process from start to finish. We piloted our interview guides with representatives of people who live with homelessness and language barriers, which helped us ask questions that really mattered and made sense to them. We held local discussion evenings to interpret the data we had collected in each neighborhood. All these approaches were far removed from the methodology I had employed in the lab, but their impact was unmistakable. This project made me a more useful scientist because I realized that the researcher is not the most important person in the room.

There’s another reason why participation matters. I’m just one researcher with very specific training, so to really embrace complexity in this new social science movement we need a much wider variety of perspectives. With An Educated Guess, I want to create a platform where all readers participate in the conversation to bring in their expertise from education and from daily life. This will allow us to:

Formulate more relevant questions and hypotheses;

Define meaningful operationalizations and measures;

Provide sources that make sense;

Interpret research data in context;

Learn from each other;

Have fun;

Repeat.

What does participation look like? At first, it’s about commenting on my posts to highlight what you liked, what you want to hear about next, and how you see the issue at hand. Please take a second to let me know in the comments below what aspect of the metacrisis you are most curious about and how it affects you. Subscribers can also drop me a note at jeroenvanbaar@substack.com—I respond to all messages.

At a later stage, I want to explore collaborative research online. With more and more data published on the internet, and with interactive coding tools such as Google Colab freely available to all, I don’t see why we can’t run a research project start to finish on An Educated Guess. Stay tuned for more on this.

Moving forward

There you have it, my little platform for a new, participatory social science, to be hosted here online. These three pillars are yet as wobbly as Bambi on ice, but they will solidify with time and practice.

When children picture their future, they attach an intuitive sense of joy to a recognizable role. In my case, this was the “prof in a lab” idea. The important part of that picture wasn’t the job title, but the underlying sense of discovery, the glee over tinkering, the excitement over sharing ideas with others. And although there are only few professors in the world, there are many people who share these feelings. These are the people I want to involve in this newsletter. By forming a community of curiosity here, online, we can all share a joy of discovery and do better science in the process.

So join me by subscribing and sharing my work with others. Let’s make many Educated Guesses together.

Next week: another data dispatch.

I recognize what you say Jeroen. Tnx for sharing.