The job of the future will be complex, and therefore frustrating

In which we discuss a second driver of workplace stress—effort-reward imbalance—and learn why the term 'burnout' was originally reserved for human service workers.

Dear readers, here is the second in a series of short posts about stress and wellbeing in the workplace. Last week we explored the impact of job control on stress, and if you haven’t seen that post yet I recommend reading it first:

Today, let’s dive into a second feature of work that has been proven to influence stress. It’s similar to job control but subtly different. I’m talking about effort-reward imbalance.

Perhaps this term already sounds familiar to you. Many of us have had the experience of working very hard to hit our annual targets only to be passed up for a promotion or bonus at the end of the year. In my field, academia, it happens often that you put your heart and soul into a paper or funding proposal, submit it, and… *crickets*… Your peers turn out not to be interested at all.

Or perhaps you’ve spent weeks putting in 110% at work every day to finish a product before a ‘hard deadline’ announced by management, only to realize that the push wasn’t needed after all. Here’s from a recent article chronicling the fate of U.S. engineers trained to work for Taiwanese microchip leader TSMC:

Several former American employees said they were not against working longer hours, but only if the tasks were meaningful. “I’d ask my manager ‘What’s your top priority,’ he’d always say ‘Everything is a priority,’” said another ex-TSMC engineer. “So, so, so, many times I would work overtime getting stuff done only to find out it wasn’t needed.” [emphasis mine]

Sounds frustrating, doesn’t it? These are good examples of an imbalance between the input and output of work, the effort and the reward. It turns out that this imbalance is another key ingredient of a highly stressful work situation. We have known this since pioneering research by German occupational health psychologist Johannes Siegrist in the 1990s.

The idea

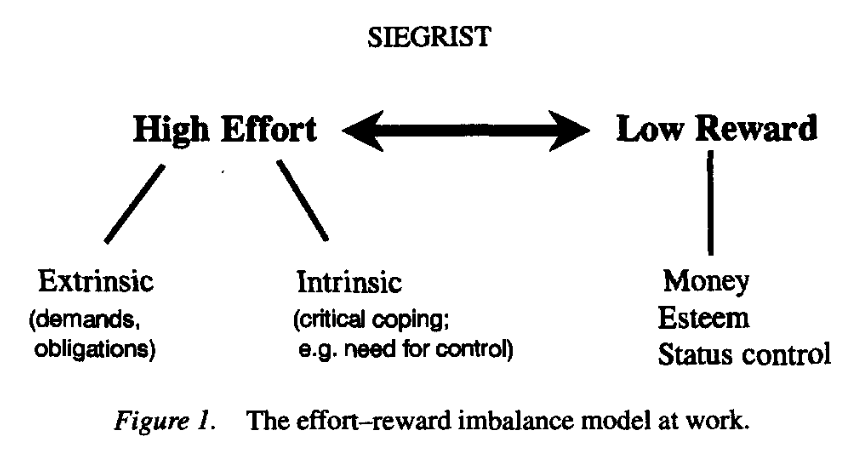

Siegrist reasoned that the job demands-control model outlined in my previous blog could not account for all variation in job stress observed in workplaces around the world. For instance, researchers observed differences in the amount of stress experienced by employees in the same rank, who enjoyed the same level of control. When looking more closely, they noticed that stress tended to be greater in workers who were highly committed to reaching a specific (ambitious) goal or who failed to realize their aspirations. This drove Siegrist to define a model of effort-reward imbalance:

In this model, high effort coupled with low reward would produce stress. High effort could arise from a few different sources: job demands, intrinsic motivation, and/or a high personal need for controlling all aspects of work (which was sometimes called a “type A” personality). Low reward usually had to do with a lack of compensation in terms of money, approval from superiors, and/or job status (promotion).

The evidence

Since Siegrist coined the idea, many studies have provided empirical evidence for the role of effort-reward imbalance. I’ll share the results from one project I consider particularly convincing. This is data from the Whitehall-II study, one of the workhorses of epidemiology. In this longitudinal project, more than 10,000 civil servants working in the Whitehall district of London completed health check-ups in the starting phase 1985-1988 and at a follow-up about 5.5 years later.

This is a powerful dataset because the participants all lived in the same city, worked in the same organization, had relatively stable jobs, and had access to the same health care and insurance system (the famous National Health Service). This meant that any differences in health trajectories observed at follow-up could reasonably be ascribed to differences in the nature of work carried out by the participants.

The researchers were particularly interested in cardiovascular and psychiatric health outcomes, because these two domains were already (theoretically) being linked to workplace stress. And guess what? At follow-up, both cardiovascular and psychiatric health issues were significantly more common in employees who expended high effort at work and saw little reward in return than in their colleagues who reported low effort and/or high reward. This effect was statistically independent of the (also important) effect of job control and a host of control variables.

The conclusion is simple. Working hard and seeing little return eats away at you, which can add up to a real health hazard over time. So if this story sounds all too familiar to you, please be careful, because effort-reward imbalance might cost you more than just everyday joy at the office.

Implications for understanding burnout

The work of civil servants in 1980s London seems alien to most of us. But even today, there is enormous variation in the degree of controllability and predictability of work.

Some jobs that act on the physical world, like mining or house painting or even knee surgery, are highly predictable. You can paint a given number of square feet of wall in a day, and you can fix a given number of knees. This is why some health care procedures are known as ‘plannable’: we know by now how much time and energy it takes to give grandma a new hip.

I’m not saying these jobs are easy. They may be technically very difficult, they may be performed under high pressure, and a cruel boss can certainly make them unbearable. But their unifying boon is a reliable relationship between effort and reward. An ophthalmologist knows how many eye exams she can administer in a day and how much she will get paid to perform them.

On the other hand, endeavors like addiction therapy and mathematical research are what I would call ‘chaotic’ jobs. Many people who enter addiction treatment relapse after they get out, so as an addiction therapist you never really know what the outcome of your sessions will be. And mathematicians often chip away at problems with no sign of progress, until—EUREKA!—the solution reveals itself to them. Just listen to Fields Medal winner Andrew Wiles, who solved a centuries-old theorem after about seven years of continuous, painstaking labor.

Inspired by Wiles, some rudimentary mathematical lingo might help us clarify the distinction. House painters and knee surgeons can be said to work on linear processes, where there is a relatively constant relationship between the input (effort) and output (reward). Addiction counsellors and mathematical researchers work on complex processes, where the outcome depends on such a large number of interacting factors that it is beyond prediction. Anyone who attempts to shape a complex system, such as a human mind or a society or the diplomatic relations between nations, has no way of knowing whether their efforts will be in vain or not.

This is the reason, perhaps, that the term ‘burnout’ was initially reserved for disillusioned human services workers. Here is from a book chapter by stress and burnout expert professor Wilmar Shaufeli (2017):

Originally, burnout was described and discussed as a phenomenon that was specific to the human service sector, and especially in health care, education, social work, psychotherapy, legal services, and law enforcement. Indeed, the original version of the MBI [burnout measurement scale] could only be employed in these fields because of its content and the wording of its questions. Until the mid-1990s, when a general version was published, burnout was more or less a phenomenon restricted to the so-called caring professions. [emphasis mine]

Why is this so? Perhaps it has to do with the great motivation and commitment found in the caring professions. But this likely interacts with the inherent uncontrollability and unpredictability of success in those fields of work.

Effort-reward reciprocity in the future of work

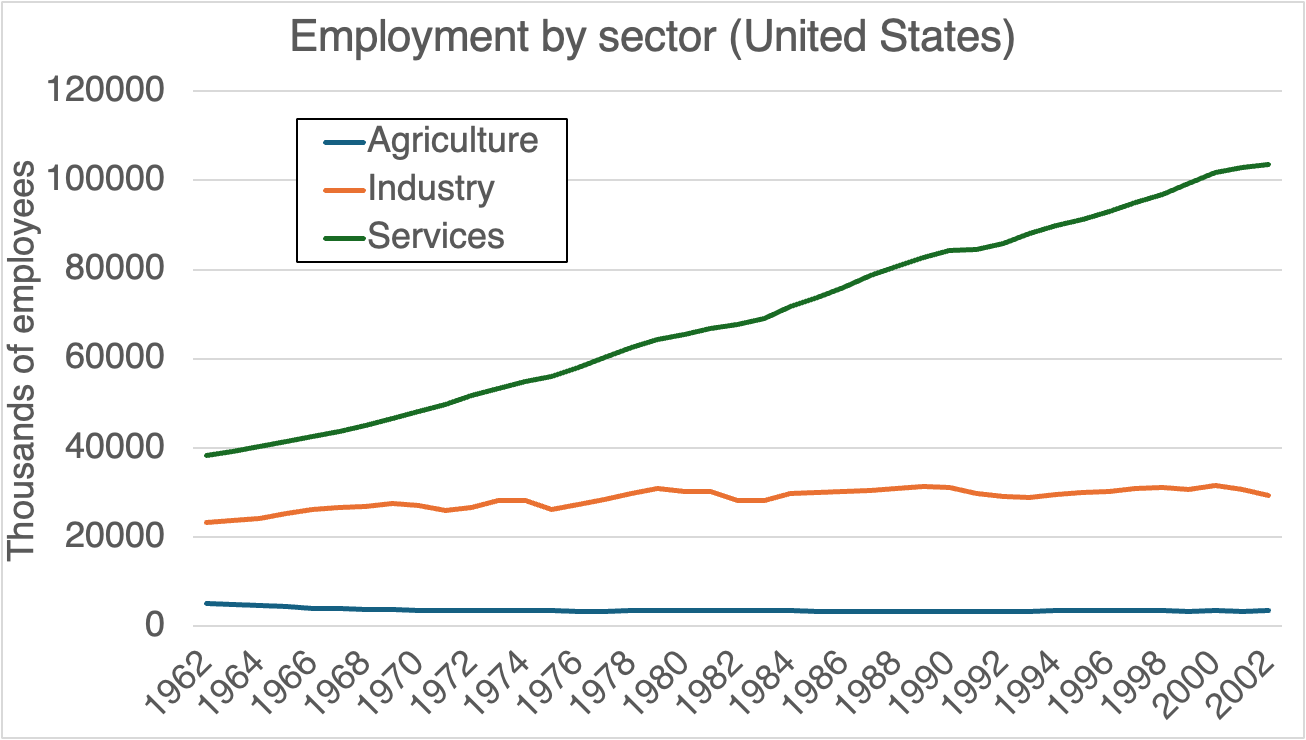

These insights place labor market developments in a fascinating new light—and bear with me here as I embark on an Educated Guess. As countries transition from agriculture- or manufacturing-based economies to service-based economies, fewer and fewer people get to work in linear jobs where efforts and rewards are in balance. And since artificial intelligence models require extensive training that maps precise efforts onto predictable rewards, A.I. will only take over jobs with reliable effort-reward relationships.

Given these two trends, what’s left for human workers in advanced economies? I think what’s left for us are complex, chaotic, human-facing jobs. In a way this is great news, because these jobs can be very meaningful and are in any case not boring. But they do require that we become skilled at resisting frustration in the face of crumbling control and predictability. Thinking back to the ‘need for control’ observed by Siegrist in his study participants, this might be an overly ambitious goal for many of us.

So, what do you think? Is the job of the future indeed more frustrating, and if so, are you ready for it? Let me know in the comments. And if this post was worth your time, leave a like below and subscribe to get notified about the next one. Thanks for reading!

Prachtige, overzichtelijke analyse!