The perplexing potential of placebos

The Christmas spirit reveals a fundamental principle of human psychology: expectations matter

Dear Educated Guessers, this is my last post before the Christmas holiday. I am taking two weeks off and will be back on January 5th. Stay tuned for some announcements about how An Educated Guess will continue in 2024. Your enthusiasm thus far has been greatly encouraging and I want to make sure I do it justice in the new year, so expect a few housekeeping updates and good news for paid subscribers.

For now, I leave you with a piece about one of my favorite psychological phenomena—the placebo effect. Sprinkled in are two movie recommendations to keep you entertained during the break. Thank you all, I hope you have a restful vacation and a heartfelt gelukkig nieuwjaar from me!

What defines the Christmas spirit?

To the cynic, Christmas is just a religious story wrapped around the pagan celebration of Midwinter. But look at the data, and you see that Christmas is a time when we actually feel merrier, are more likely to share with others, and even call truces with our sworn enemies.

What unites these observations is that they happen because we expect them to. The Christmas feeling is created out of thin air, year after year. It’s propped up by our expectations, whipped up by seasonal decorations and holiday hits on the radio. The more we lean into these triggers, the better our mood, and the more we end up doing good.

This notion is explored in the classic holiday film Elf (2003), in which Santa’s sleigh runs on magical Christmas Spirit as measured by the Clausometer. In a key scene, Zooey Deschanel’s character starts a mass caroling event in Central Park, giving Santa the boost he needs to take off and deliver his presents. The message is clear: if you believe, it will happen—so just shut up and sing already!

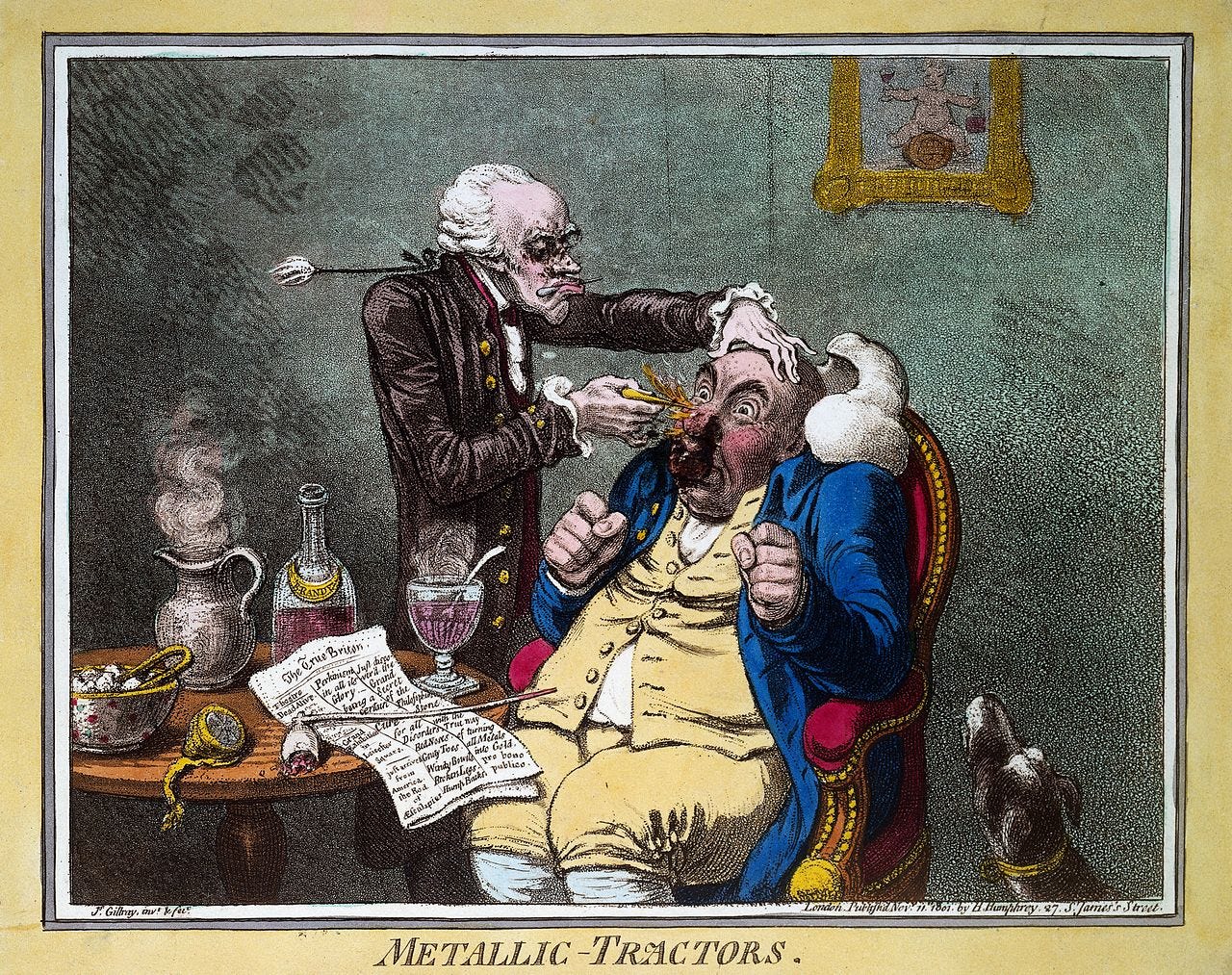

As other bloggers have noted, the storyline of Elf captures the notion of the placebo effect. In medicine, a placebo is a sham treatment that can have very real effects. It was first demonstrated by English doctor John Haygarth in 1799, who experimented with a popular (but fake) treatment of the time known as “Perkins tractors”. These tractors were little metal rods, which one would pass over the skin to supposedly affect an electrically charged fluid thought to cause pain. Haygarth created fake rods made out of wood, passed them over the skin of patients, and recorded results just as good as those obtained with real Perkins tractors. Haygarth wrote down his findings in the aptly titled book On the Imagination as a Cause & as a Cure of Disorders of the Body.

Haygarth had a critical insight about placebos. He did not try to show that both the Perkins tractors and his wooden replicas were totally ineffective. Instead, he showed that the real and fake tractors were both a little effective, but only because the patient imagined them to be.

In recent years, scientists have built upon Haygarth’s early findings to show that placebos don’t just alter your subjective perception of pain, but also the underlying physiology. This happens at multiple stages of the nervous system, from skin to brain. Under placebo, people sweat less when receiving a painful stimulus; pain-sensitive nerve cells in the spinal cord are less responsive; and neural activation in pain-related brain regions is reduced. Placebo effects extend to psychological pain, too: depression can be reduced by sham treatments.

I want to be clear here that we should not overestimate the potential of placebos. Obviously, there are many things they can’t cure, and reducing pain is not the same as taking its source away. Yet, the above evidence demonstrates that our imagination has a powerful influence on how we function and feel, which opens new doors for improving our quality of life. Just as with the Christmas spirit, would it not be smart to lean in and use that power? To help you do so, I will go over three of the most fascinating recent findings about the placebo effect. Perhaps they will inspire you to use the power of expectations to improve your own life.

Level 1. Raising your own expectations.

Now that you know placebos work, you might wonder how we can strengthen their beneficial effects. The answer is simple: raise your expectations.

A team of researchers from McGill University and Harvard University demonstrated this in a clever experiment. They capitalized on the fact that there is a lot of hype around personalized treatment in modern medicine. If you have diabetes or cancer, for instance, it is thought that prescribing a unique treatment that matches your genes or behavior patterns might be more effective than prescribing a generic treatment.

The researchers invited about a hundred participants to their lab at McGill and subjected them to painful heat stimulation on their forearm. However, the participants were also hooked up to a separate device—a fancy-looking but totally fake piece of equipment—that was supposed to reduce their pain. Here’s what the anti-pain machine looked like:

The participants were then divided into two groups. The one group was told that this machine would reduce their pain generically, even though it wouldn’t—a classic placebo. But the second group was told that the machine was adjusted to their personal genetic makeup and physiological response patterns. The second group, therefore, received a personalized placebo treatment.

The results of the study showed that the generic placebo reduced pain by about 3%, but the personalized placebo reduced pain by about 11%. It was even observed that participants who had a stronger need for uniqueness—measured by a scale with items such as “When I am in a group of strangers, I am not reluctant to express my opinion publicly”—benefited more from the personalized placebo. These results suggest that convincing someone a placebo is made especially for them can make it more effective.

Level 2. Raising your doctor’s expectations.

In the previous study, we saw that the more you believe a sham treatment will reduce your pain, the more it will. But in real-life medical settings, the patient rarely knows how effective a treatment will be, and the expectations of the doctor might matter more. This is why medical trials must be double-blinded, where neither the patient nor the doctor knows whether a real medicine was given. Building on this knowledge, would it be possible to manipulate the beliefs of a doctor about the effectiveness of a placebo treatment—and would this even impact the effectiveness experienced by the patient?

A team of researchers from Dartmouth College put this question to the test.1 They set up an experiment in which participants—known as “patients”—would receive painful heat stimulation on their forearm. The pain was delivered after one of two creams was applied to the patient’s skin: either a pain-reducing cream called thermedol or a placebo cream. But there are two kickers. First, both creams were identical and not effective against pain. And two: the patient did not know which cream was the supposedly effective thermedol and which was the placebo. This was only known by another participant—the “doctor”—who applied the cream to the patient’s arm. Before the experiment, the doctor had tried the two creams himself, during which a weaker pain stimulation was secretly given while the doctor had used thermedol. This led the doctors to believe theremedol was effective against pain, even though it wasn’t, which could then be used to test whether the doctor’s expectation could be transmitted to the patient.

Are you still following me? It’s a complicated experiment. But the bottom line is that the patient had no idea which cream was supposedly the real one, only the doctor did. And yet, even though both creams were identical, the patients felt less pain when receiving the cream the doctor thought was real! This did not just extend to the patients’ subjective pain ratings, but also to their sweat response to the pain, as measured by the skin conductance response (SCR):

How did the doctor’s expectations affect the patient’s pain response? The researchers recorded facial expressions of both participants using GoPro headsets, and found that the doctor’s facial expressions were subtly different when they thought they were applying a real pain-reducing cream. We can speculate as to what was going on inside the doctor’s mind at the time: presumably, they felt relaxed knowing that they could actually help the patient. In this way, even a fake treatment can be a little effective against pain as long as the doctor believes it’s real.

Level 3. Raising everyone else’s expectations.

So far, we saw that if you believe your pain treatment is personalized, it’s extra effective, even if it’s actually a placebo. And we saw that if your doctor believes your pain treatment is effective, even if it’s not, it can be a strong placebo as well. In all these cases, there is an element of deception: someone believes something that is actually not true. What if we took that element away?

Bafflingly, it has now been shown repeatedly that placebos even work if you tell people they are placebos. This was famously demonstrated in a study on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The researchers invited 80 patients with IBS to their lab at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. They told everyone that some participants (group 1) would receive a placebo treatment, which consisted in taking a non-effective pill twice a day. These placebo pills were truthfully described as “inert or inactive pills, like sugar pills, without any medication in it”. However, the patients were also told that “placebo pills, something like sugar pills, have been shown in rigorous clinical testing to produce significant mind-body self-healing processes.” Group 2 received no pills at all, but still had the same conversations with the treatment providers. Amazingly, group 1—who knew they ate a placebo pill twice a day—still reported greater reduction in IBS symptoms than group 2.

Why does this happen? Some researchers have tried to explain it using learning theory, claiming that cues of treatment such as a medical setting, taking a pill etc. may trigger learned associations in the brain that can cause physiological changes. Another explanation, though, is that the expectations of treatment effects reduce negative emotions and thereby reduce symptoms such as pain. People expect placebos to be effective, so they feel that they’re in good hands. They can relax. In psychological therapy, in fact, this element of “being in good hands”—trusting the therapist, believing in the effectiveness of the treatment, and so on—is thought to be one of the most (if not the only) effective elements of therapy.

This fits with the finding that placebo effects have gotten stronger over time, both in general medicine and in psychiatry. Perhaps this is explained by the fact that the placebo effect has become more well-known over time, or by increased trust in the medical system overall. So now that everyone knows about the placebo effect, we can actually start using it to distribute this “in good hands” feeling more broadly, even for treatment-resistant issues like IBS.

Just as with the Christmas spirit, the medical system has managed to create faith in treatment out of thin air—and this has become so effective that it even works when you tell people it doesn’t.

How can we apply the placebo effect in daily life? Let me share three potential takeaways, and please leave a comment if you think of another one.

First, expectations are powerful, yet fragile. If effectiveness is dependent on beliefs, and beliefs can change on a whim—then we should be very careful with what we believe, right? For instance, more and more teenagers experience anxiety today, which has led some (including myself) to speak of a mental health crisis. But given the placebo evidence listed above, telling everyone we are in crisis mode might rob teenagers from the feeling of “being in good hands”, which could drive up rates of mental health problems. This is a touchy point, because we should never lie about the mental health issues many are experiencing today. But as long as we don’t understand what causes mental illness (and we don’t), it would be healthy to spread confidence and optimism in addition to caution.

Second, be confident, even if you are unsure. This is, of course, easier said than done. In modern life, it seems like we know and control so many aspects of our lives—from fertility to where the traffic jams are—that it becomes harder to cope with what we can’t control. In the past, people may have addressed lack of control with religious beliefs, trusting in God’s plan. But this religious expectation of safety has become more and more elusive in modern times. To reap the benefits of expectation effects, we need new ways to find confidence in uncertainty. So instead of making “do better” your New Year’s resolution, why not reflect on ways you can become more trusting or even healthily gullible in 2024?

Third—and especially relevant around Christmas time—the placebo effect teaches us something about the roles we can play for others. If a parent believes a child will be in pain, this expectation can end up strengthening the pain; and if a parent believes that “kissing it better” helps their kid, it will! A parent’s role is to convey confidence, against all odds. The same goes for teachers, bosses, and other positions of responsibility and aid. In 2024, let’s be confident supports for others wherever possible, because you never know who’ll need it.

So let me leave you with a great example of this confident parenting style. It’s found in one of the greatest Italian movies of the last few decades, La vita è bella (Life is beautiful). If you haven’t seen this film, please do so over the holidays—and you will be sure to feel the Christmas spirit.

An Educated Guess is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. And if this post has been worth your time, share it with someone else to keep the newsletter going. Thank you! ~Jeroen

I was fortunate enough to visit this lab as a graduate student while the study was going on. The doctor-patient manipulation was very convincing; the participants even wore fitting lab coats and scrubs to match their role!